The Battle of the Boyne

In 1690, a significant historical event known as the Battle of the Boyne took place. This pivotal conflict occurred between two prominent figures, the Catholic King James II and the Protestant King William III, who had previously deposed James from the English throne in 1688. The battle itself was fought at Oldbridge on the banks of the River Boyne, and its outcome marked a decisive victory for King William III.

The Battle of the Boyne played a crucial role in shaping the course of history. By thwarting James II's efforts to reclaim the British crown, William III's triumph solidified the establishment of Protestant dominance in Ireland. This victory proved to be a turning point in the struggle for power and religious influence in the region.

The consequences of the battle reverberated far beyond the immediate context. The impact of this momentous event ensured the preservation and continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland for years to come. The conflict's significance lies not only in its military outcome but also in its broader implications for the social and political landscape of Ireland and Britain.

The battle took place on July 1st 1690 in the Julian calendar. This was equivalent to July 11th in the new style (Gregorian) calendar, although today its commemoration is held on July 12th.

William's forces defeated James's army of mostly raw recruits. The symbolic importance of this battle has made it one of the best-known battles in the history of the British Isles and a key part of the folklore of the Orange Order. Its commemoration today is principally by the Protestant Orange Institution in Northern Ireland.

Lead up to the Battle of the Boyne

The battle was the decisive encounter in a war that was primarily about James's attempt to regain the thrones of England and Scotland, resulting from the Immortal Seven's invitation to James's daughter and William's wife, Mary, to take the throne. It is especially remembered as a crucial moment in the struggle between Irish Protestant and Catholic interests.

In an Irish context, however, the war was a sectarian and ethnic conflict, in many ways a re-run of the Irish Confederate Wars of 50 years earlier. For the Jacobites, the war was fought for Irish sovereignty, religious toleration for Catholicism, and land ownership. The Catholic upper classes had lost almost all their lands after Cromwell's conquest, as well as the right to hold public office, practice their religion, and sit in the Irish Parliament. They saw the Catholic King James as a means of redressing these grievances and securing the autonomy of Ireland from England. To these ends, under Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnel, they had raised an army to restore James after the Glorious Revolution. By 1690, they controlled all of Ireland except for the province of Ulster. Most of James II's troops at the Boyne were Irish Catholics.

The majority of Irish people were "Jacobites" and supported James II due to his 1687 Declaration of Indulgence or, as it is also known, The Declaration for the Liberty of Conscience, that granted religious freedom to all denominations in England and Scotland and also due to James II's promise to the Irish Parliament of an eventual right to self-determination

Conversely, for the Williamites, the war was about maintaining Protestant and English rule in Ireland. They feared for their lives and their property if James and his Catholic supporters were to rule Ireland. In particular, they feared a repeat of the Irish Rebellion of 1641, which had been marked by widespread killings. For these reasons, Protestants fought en masse for William of Orange. Many Williamite troops at the Boyne, including their very effective irregular cavalry, were Protestants from Ulster, who called themselves "Inniskillingers" and were referred to by contemporaries as "Scots-Irish".

Commanders

The opposing armies in the battle were led by the Roman Catholic King James II of England, Scotland, and Ireland and opposing him, his nephew and son-in-law, the Protestant King William III ("William of Orange") who had deposed James the previous year. James's supporters controlled much of Ireland and the Irish Parliament. James also enjoyed the support of his cousin, Louis XIV, who did not want to see a hostile monarch on the throne of England. Louis sent 6,000 French troops to Ireland to support the Irish Jacobites. William was already Stadtholder of the Netherlands and was able to call on Dutch and allied troops from Europe as well as England and Scotland.

James was a seasoned officer who had proven his bravery when fighting for his brother, King Charles II, in Europe, notably at the Battle of the Dunes (1658). However, recent historians have noted that he was prone to panicking under pressure and making rash decisions, possibly due to the onset of the dementia which would overtake him completely in later years. William, although a seasoned commander, was hardly one of history's great generals and had yet to win a major battle.

Many of his battles ended in stalemates, prompting at least one modern historian to argue that William lacked an ability to manage armies in the thick of conflict. William's success against the French had been reliant upon tactical maneuvers and good diplomacy rather than force. His diplomacy had assembled the League of Augsburg, a multi-national coalition formed to resist French aggression in Europe. From William's point of view, his takeover of power in England and the ensuing campaign in Ireland was just another front in the war against King Louis XIV.

James II's subordinate commanders were Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, who was Lord Deputy of Ireland and James's most powerful supporter in Ireland, and the French general Lauzun. William's second-in-command was the Duke of Schomberg, a 75 year old professional soldier. Born in Heidelberg, Germany, Schomberg had formerly been a Marshal of France, but, being a Huguenot, was compelled to leave France in 1685 because of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Armies

The Williamite army at the Boyne was about 36,000 strong, composed of troops from many countries. Around 20,000 troops had been in Ireland since 1689, commanded by Schomberg. William himself arrived with another 16,000 in June 1690. William's troops were generally far better trained and equipped than James's. The best Williamite infantry were from Denmark and the Netherlands, professional soldiers equipped with the latest flintlock muskets.

There was also a large contingent of French Huguenot troops fighting with the Williamites. William did not have a high opinion of his English and Scottish troops, with the exception of the Ulster Protestant irregulars who had held Ulster in the previous year. The English and Scottish troops were felt to be politically unreliable, since James had been their legitimate monarch up to a year before. Moreover, they had only been raised recently and had seen little battle action.

The Jacobites were 24,000 strong. James had several regiments of French troops, but most of his manpower was provided by Irish Catholics. The Jacobites' Irish cavalry, who were recruited from among the dispossessed Irish gentry, proved themselves to be high caliber troops during the course of the battle. However, the Irish infantry, predominantly peasants who had been pressed into service, were not trained soldiers. They had been hastily trained, poorly equipped, and only a minority of them had functional muskets. In fact, some of them carried only farm implements such as scythes at the Boyne. On top of that, the Jacobite infantry who actually had firearms were all equipped with the obsolete matchlock musket.

The Battle

William had landed in Carrickfergus in Ulster on June 14th 1690 and marched south to take Dublin. James chose to place his line of defense on the River Boyne, around 48 km (30 miles) from Dublin. The Williamites reached the Boyne on June 29th. The day before the battle, William himself had a narrow escape when he was wounded in the shoulder by Jacobite cannon ball while surveying the fords over which his troops would cross the Boyne.

The battle itself was fought on July 1st (Julian calendar) July 11th (Gregorian calendar), for control of a ford on the Boyne near Drogheda, about 2.5 km (1.6 miles) northwest of the hamlet of Oldbridge (and about 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) west-northwest of the modern Boyne River Bridge). William sent about a quarter of his men to cross the river at Roughgrange, about 4 km (2.5 miles) west of Donore and about 9.7 km (6 miles) southwest of Oldbridge.

The Duke of Schomberg's son, Meinhardt, led this crossing, which Irish dragoons in picquet under Neil O'Neill unsuccessfully opposed. James, an inexperienced general, thought that he might be outflanked and sent two thirds of his troops, along with most of his artillery, to counter this move. What neither side had realized was that there was a deep, swampy ravine at Roughgrange. Because of this ravine, the opposing forces there could not engage each other, but literally sat out the battle. The Williamite forces went on a long detour march which, later in the day, almost saw them cut off the Jacobite retreat at the village of Naul.

At the main ford near Oldbridge, William's infantry, led by the elite Dutch Blue Guards, forced their way across the river, using their superior firepower to slowly drive back the enemy foot soldiers, but were pinned down when the Jacobite cavalry counter-attacked. Having secured the village of Oldbridge, some Williamite infantry tried to hold off successive cavalry attacks with disciplined volley fire, but were scattered and driven into the river, with the exception of the Blue Guards. William's second-in-command, the Duke of Schomberg, and George Walker were killed in this phase of the battle.

The Williamites were not able to resume their advance until their own horsemen managed to cross the river and, after being badly mauled, managed to hold off the Jacobite cavalry until they retired and regrouped at Donore, where they once again put up stiff resistance before retiring. The Jacobites retired in good order. William had a chance to trap them as they retreated across the River Nanny at Duleek, but his troops were held up by a successful rear-guard action.

The casualty figures of the battle were relatively low for a battle of 60,000 participants, about 2,000 died. Although three-quarters of them were Jacobites, William's army had far more wounded. At the time, most casualties of battles tended to be inflicted in the pursuit of an already-beaten enemy. This did not happen at the Boyne, as the counter-attacks of the skilled Jacobite cavalry screened the retreat of the rest of their army. The Jacobites were badly demoralized by the order to retreat, which lost them the battle. Many of the Irish infantrymen deserted. The Williamites triumphantly marched into Dublin two days after the battle. The Jacobite army abandoned the city and marched to Limerick, behind the River Shannon, where they were unsuccessfully besieged.

After his defeat, James did not stay in Dublin, but rode with a small escort to Duncannon and returned to exile in France, even though his army left the field relatively unscathed. James's loss of nerve and speedy exit from the battlefield enraged his Irish supporters, who fought on until the Treaty of Limerick in 1691.

Aftermath

The battle was overshadowed in its time in England by the defeat of an Anglo-Dutch fleet by the French two days later at the Battle of Beachy Head, a far more serious event in the short term. Only on the continent was the Boyne treated as an important victory. Its importance lay in the fact that it was the first proper victory for the League of Augsburg, the first-ever alliance between the Vatican and Protestant countries. Thus the victory motivated more nations to join the alliance and in effect ended the fear of a French conquest of Europe.

The Boyne also had strategic significance for both England and Ireland. It marked the end of James's hope of regaining his throne by military means and probably assured the triumph of the Glorious Revolution. In Scotland, news of this defeat temporarily silenced the Highlanders supporting the Jacobite Rising, which Bonnie Dundee had led. In Ireland, the Boyne fully assured the Jacobites that they could successfully resist William. But it was a general victory for William, and is still celebrated by the Protestant Orange Order on the Twelfth of July.

The Treaty of Limerick was written first and was very generous to Catholics. It allowed most land owners to keep their land so long as they swore allegiance to William of Orange. It also said that James could take a certain number of his soldiers and go back to France. However, Protestants in England were annoyed with this kind treatment towards the Catholics, especially when they were gaining strength and money. Because of this, the penal laws were introduced. These laws included banning Catholics from owning weapons, reducing their land, and prohibiting them from working in the legal profession.

Commemoration

Originally, Irish Protestants commemorated the Battle of Aughrim on July 12th (old style, equivalent to July 22nd new style), symbolizing their victory in the Williamite war in Ireland. At Aughrim, which took place a year after the Boyne, the Jacobite army was destroyed, deciding the war in the Williamites' favor. The Boyne, which in the old Julian calendar took place on July 1st, was treated as less important, third after Aughrim and the anniversary of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 on October 23rd. What was celebrated on "The Twelfth" was not William's victory at the Battle of the Boyne, but the defeat of the Catholic Irish at Aughrim, thereby ending the fear of having to surrender the planted lands.

In 1752, the Gregorian calendar was adopted in Ireland, which erroneously placed the Boyne on July 12th instead of Aughrim (the correct equivalent date was July 11th). However, even after this date, "The Twelfth" still commemorated Aughrim. But after the Orange Order was founded in 1795 amid sectarian violence in Armagh, the focus of parades on July 12th switched to the Battle of the Boyne.

Being suspicious of anything with Papist connotations, however, rather than shift the anniversary of the Boyne to the new July 1st or celebrate the new anniversary of Aughrim, the Orangemen continued to march on July 12th.

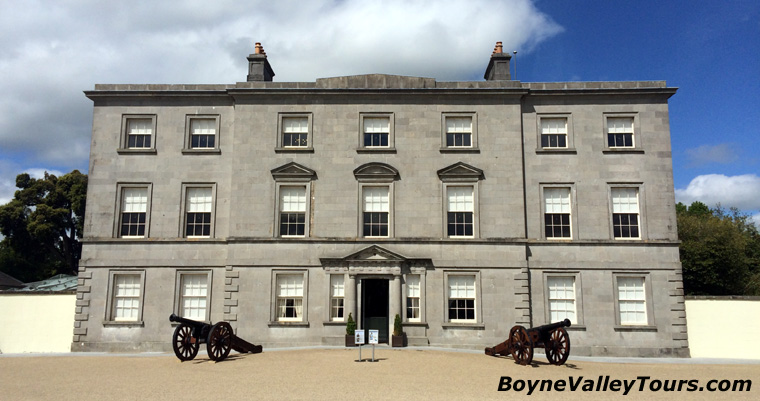

Oldbridge - Battle of the Boyne site

The site of the Battle of the Boyne covers a wide area west of the town of Drogheda. The Interpretive Center at Oldbridge House is about 1 mile (1.6 km) to the west of the main crossing point. On April 4th 2007 in a sign of improving relations between unionist and nationalist groups, the newly elected First Minister of Northern Ireland, the Reverend Ian Paisley, was invited to visit the battle site by the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern later in the year. Following the invitation, Paisley commented that "such a visit would help to demonstrate how far we have come when we can celebrate and learn from the past so the next generation more clearly understands." On May 10th the visit took place, and Paisley presented the Taoiseach with a Jacobite musket in return for Ahern's gift at the St Andrews talks of a walnut bowl made from a tree from the site. A new tree was also planted in the grounds of Oldbridge House by the two politicians to mark the occasion.

Victorian Walled Garden - Battle of the Boyne Visitor Center Oldbridge House

Victorian Walled Garden - Battle of the Boyne Visitor Center Oldbridge House